Tales from the Dungheap

The following is a text to accompany Sebastian Jefford’s exhibition ‘Toy’ at Galerie Noah Klink Gallery in Berlin (02.05. – 31.05.2025)

We must not be afraid to depict our time, just because it is our time.

— Honoré Daumier

"So cute! These are great! Thank you so much for sharing!"

These saccharine response 'buttons' are a hundred bits of information amongst a quadrillion more, saturating the global brain. Gmail suggested I use them in response to images Seb sent me – the drawings in this exhibition. In the sprawling corporate dung heap – our contemporary megalopolis – phoney goals and challenges form the discipline regimen of our society. As Harry Frankfurt or David Graeber would attest, we live in bullshit. For Frankfurt, bullshit is not just a lie; it's a lie both the liar and the lied-to know, but they participate willingly regardless. The truth is no longer a concealed insurgent; it is simply irrelevant. For Graeber, bullshit jobs are the contradiction at the core of capitalist society: that as efficiency grows, jobs can't decrease; perversely, legions of the professional managerial class parasitise the niche of growing profits. In stupefied glee and numb transparency, reeling from the whip hand of debt, political discourse and social relations have succumbed to the shadow economy of attention.

The acid bath of individualism has dissolved individuals. The attention economy is both an antidepressant and an amphetamine, designed to confuse and electroshock its subjects, to distract them from the fact that they are getting poorer. Steve Bannon, one of the most repugnant denizens in the sewer of public life, has the dictum: "flood the zone with shit". In the pandemonium, the weak suffer what they must, whilst fixating on illusory objectives of behaviourist reward and punishment. But to what end does this supposed productivity driven society equilibrate, if not efficiency and rationality? In the 'zone of shit', it is time that forms the law.

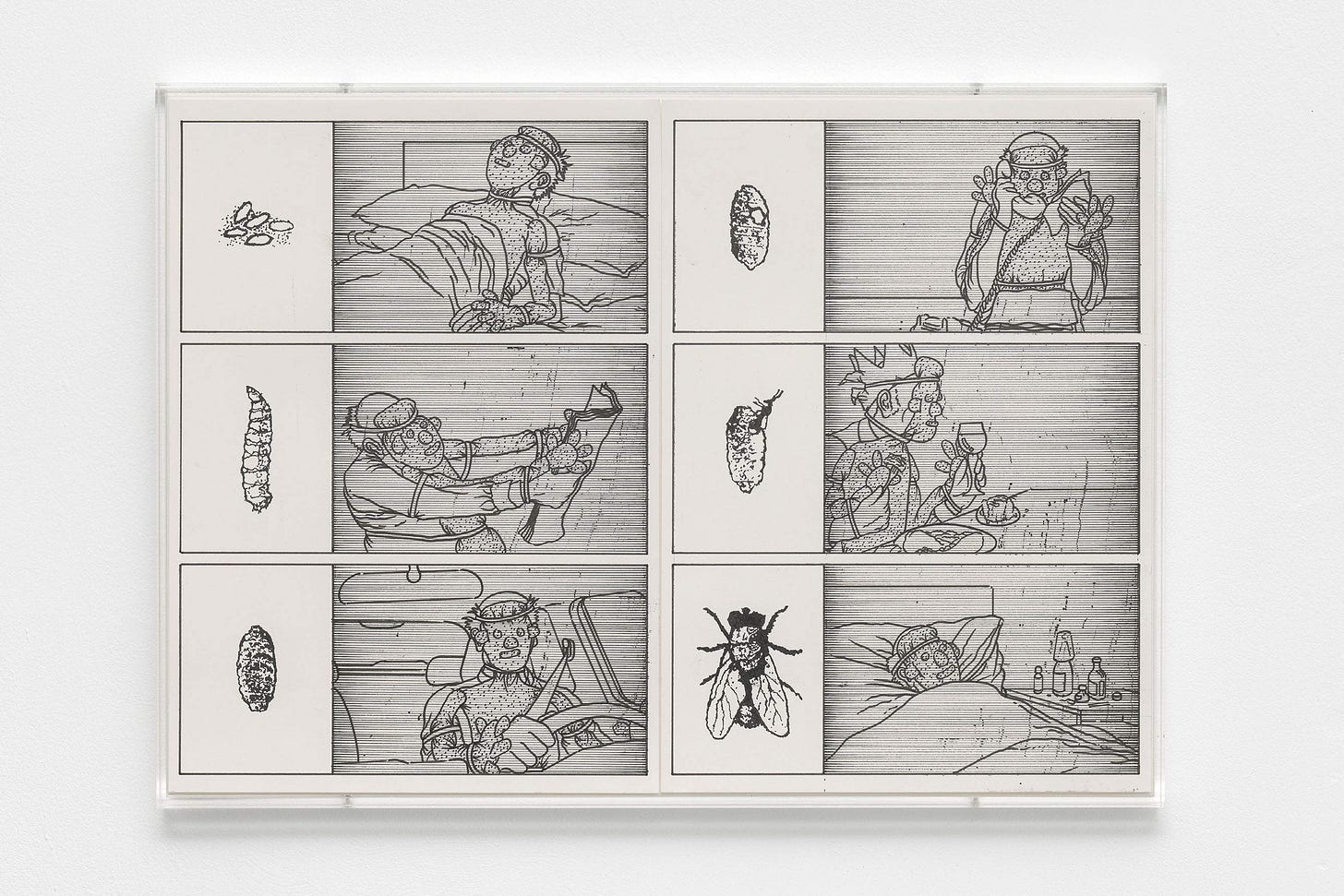

‘Life Cycle of a Fly’ 2025

Time is money! In a bullshit economy, the time extracted from the labour force is a punitive end in itself; productivity and value become a vague superstition – endless meetings and emails that just run down the clock. Culture, too, has assumed this incentive structure of homo-economicus. It is embarrassed by the myth of the genius, but not by the avatar of neoclassical economics. Is it not the rational utility-maximising agent who is invoked as the 'viewer'? The aspiration of 'creativity' is a camouflaged synonym for having more time, sold as a religious indulgence to those who can afford it; it purports to cure the ailment of waning political agency.

"So cute! These are great! Thank you so much for sharing!"

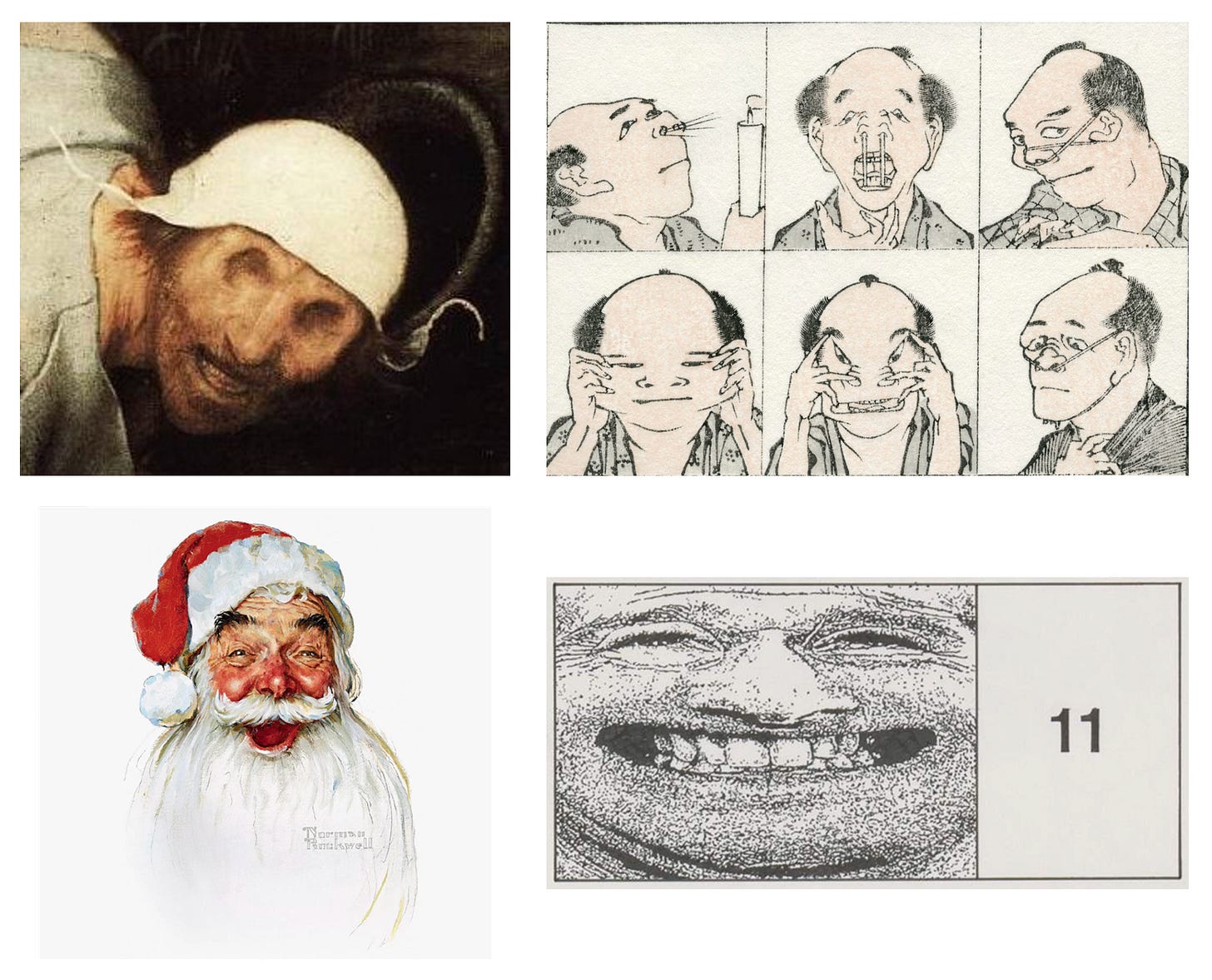

But enough complaining – it's the world we are in. Carl Jung suggested if we encounter shit in our dreams to approach it, because it's gold in disguise. Seb is something of a scatological alchemist, unknotting the mass parasocial wire-heading with plasticine and a felt tip pen. Daumier said drawing is the "medium of the proletariat"; it costs nothing and is wilfully antithetical to intellectual grandstanding. The forms of resistance sold in the PhD-industrial-complex – detournement, critique, praxis and academic posturing – have no relevance to the caricaturist. They have no allegiances, least of all to other artists. They are, however, a talisman for others. De Kooning owed a debt to commercial artists; he loved Norman Rockwell as much as Rubens, and the great Hokusai saw no contradiction between high and low art – he wrote "how to draw" books for a mass audience.

Clockwise: Pieter Bruegel the Elder (detail) 1568, Katsushika Hokusai 1814, Sebastian Jefford (detail) 2025, Norman Rockwell 1942

Comics, particularly have a defiance over and above their pompous cousin, painting. Painting warps time into a replenishing present. For comics, the hourglass runs down, but we donate our time willingly – the comic is a reclamation of the tyrannical clock of work. It is the medium of children and the incarcerated. Through its grubby trickery, it cajoles the political ruling class precisely because it demands no moral obligation to the reader. Cartoonists often adopt a deliberately lower status than their readers; yet we all wear the fool's cap when surveying lewd doodles cast out from the Diogenean wine jar, no matter how correct the politics. Despite being effluent from the semicolon of the unconscious, cartoons are the highest form of conceptual art. Their abiogenesis reveals semantic rules in a much loftier psychic parameter space than the neologisms of Joseph Kosuth. Was it not the genius Charles Sanders Peirce who devised his semiotics by doodling eyeballs, weights, and a strawberry with a pin through it? The cartoonist is to conceptual art as biology is to chemistry: the unspoiled geometry of electron shells transmogrifies into a methane-saturated compost. Seb extracts the wriggling creatures and proceeds to catalogue them, under the loony-tunes microscope of his consciousness.

Charles Sanders Peirce 1870, Sebastian Jefford (Detail) 2025

These protagonists are a motley crew of buffoons, delinquents, and dead legs – a cast of characters with a family resemblance to Richard D. James' warped grimace, Goya's brainsick and Brueghel's soiled peasants. Helpless in their infantilisation, daily tasks are an unbearably banal torture: driving a car or eating breakfast. There are no speech bubbles; the machinations of his farcical world all happen in silence. Society is portrayed as a surveillance hellscape: force feedings, endless locomotion, interminable repetition. Seb caricatures a society that can't have an existential crisis - there isn't time. The abyss, in all its terror, has been castrated, pathologized into medical acronyms, doled out by well-meaning health workers. “Open your mouth, here comes the choo-choo train!”

In one work, the psyche of the artist is splintering into twenty-two grimacing heads, resembling the souvenir tea towels children make at primary school in the UK. Doodled self-portraits are collected and printed – a fabric rectangle containing a class of potato head smiley faces. It's a formative moment for many child artists: to contemplate the effigy of one's own face in its society of misshapen compatriots: a primordial soup of equality, ignorant to the predation of an economy. This uneasy memory is turbocharged; the innocent children have grown up. A quasi government-credit card-social media amalgamation is spying on the subjects, locked into their respective data windows; extreme g-force is applied – a torture of distilled speed and acceleration.

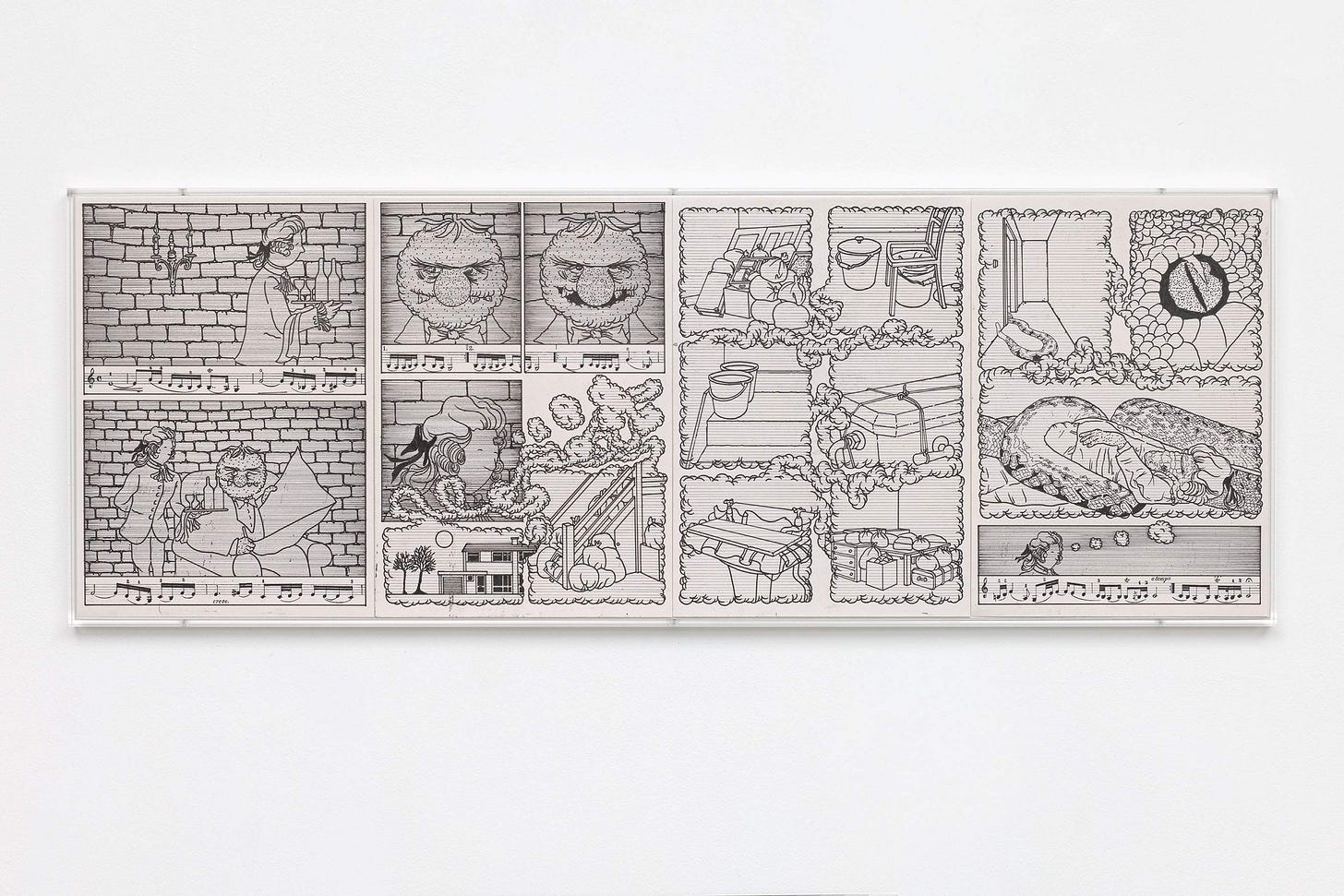

In another work, 'The Little Gentleman', a meat-faced tycoon of industry is dressed in his evening suit, reading his broadsheet newspaper with a lobotomised gurn. A young porter, dressed in Georgian attire, presents the carbuncle with an aperitif. The porter daydreams; his thought bubbles forming ribbons of a duodenum in synchrony with the musical notes to Bach's "Air on a G String." In front of the tycoon of industry, the porter is absent. His mind's eye is remote viewing – a psychic technique taught by the US military to spy on Russia during the Cold War.

The daydream slithers into an abandoned house. It glides over barricades of musty, sweet-smelling rubbish, tasting with sensate whiskers like a phantom trilobite. The porter's mind detects bitter urea crystals, ketchup and bleach. The sink and toilet have been stopped up with makeshift string and planks of wood to stop the passage of any waste leaving the building – or entering. Another bucket under a chair is lined with a carrier bag; the seat panel has been removed. Past this makeshift shitter, an anaconda is revealed. The porter is fantasising now: as the snake's giant, monstrous body is revealed, its hubcap eye flashes. Immobile, apart from the peristaltic undulations of the digestive tract, the imagined tycoon is being consumed – the body undergoing a concealed evisceration soaked in concentrated hydrochloric acid and pepsin, the juices of the distended stomach. Back in reality, the music is still playing; the tycoon sips his cognac, and the porter quietly excuses himself.

‘The Little Gentleman’ 2025

After ruminating on the works in the exhibition, including the giant polyurethane moon-heads below the tiled architrave, we sense an obfuscation of the artist, his disappearance, melting through the cast iron sluice of a storm drain. This is not a conceited retreat, much the opposite: to truly explore the imagination is to abseil within and forget oneself. Through Seb's works, images overflow from a hidden spring which many have forgotten. Too often art abandons the crucible of the imagination – the molten fission reactor ruled by esoteric laws as strict as those of cosmology. This is because, analogous to the porter’s daydream, the conformity of the bullshit society has transgressed the blood brain barrier: culture has imbibed the malady of utility to a chronic degree. To be free, the artist must submit to the imagination and acknowledge their servitude, allow it to feed on their jangling storm of neurons as it pleases. Only then can perversions and symptoms comingle in their incubation alongside nobler aspirations. All artists can hope to achieve is to find a minuscule opening in the world – a single capillary in the vast Googleplex of relations – connecting their mind and body like a fibre-optic cable to those dynamic forms that zip around at light speed in clandestine objectivity. For, as Wittgenstein said about philosophy, art has the form: "I know not my way about”.

Text by Sean Steadman