Competence and Decency

The following is an exhibition text for Sebastian Jefford’s exhibition ‘Competence and Decency’ at Galleri Opdahl in Stavanger, Norway, which runs from 17.10.25–22.11.25.

‘Thank your lucky stars’, 2025

In 1662, Claude Le Petit, a French lawyer and libertine poet who penned satirical rhymes against the Church and Crown, was condemned to death. In a moment resembling comic verse, the papers on his desk blew through an open window and landed at the feet of a priest. Upon reading them, the clergyman discovered profanities regarding the Virgin Mary. Le Petit was reported to the authorities immediately; his apartment was searched and his notebooks seized. His trial was hurried, and his appeal rejected. Le Petit’s fate was entwined with that of a figure he had written poems to valorise, a certain Chausson, who was burned alive for sodomy and, in a final act of resolve, rejected the cross, baring his arse to the audience of his immolation. Le Petit’s own demise was accented by the executioner chopping free the instrument of his crime, his writing hand, before performing strangulation and burning. Witnesses remarked on what a waste it was for a witty talent to die in such a manner, and so young.

Such barbarism seems an anachronism of unenlightened history. Yet the body politic perennially requires obsessive cleansing rituals. As Foucault acknowledged, and poor Le Petit suffered, the flesh ultimately pays the debt owed by the immaterial creditor of speaking freely. The habit of sympathetic witchcraft is a deep subroutine in the human psyche, believing the soul can be scrubbed clean by desecrating the body, a fetish object, or a sacrificial animal. Nowhere is this truer than in art! Contemporary politics are not exempt either. Statecraft, even when practised in good faith, is rarely rational argument. It is mostly magical thinking, purification rites performed publicly and intended to galvanise tribal unity. A harmonious society is one where the theatre of this preening custom is interpreted as a good in itself; where even iconoclasm is welcomed as an immunological function.

Authoritarianism has a pathological obsession with purifying the cleansing ritual of itself. It is politics as cynical automation; as Hannah Arendt recognised, consistency is demanded even at the expense of basic reality. If the coordinates of the psychic lifeworld deflate to a zero-sum conspiracy theory, then censorship inverts. When the authorities are deliberately grotesque, the cartoonist is somewhat castrated and now satirises for some semblance of moral decency. The blasphemer is turned evangelist. Power no longer wears the pronounced regalia of the judiciary; it is disguised as a crackpot internet personality. Tyrannical paternalism morphs into capricious teenage whimsy. In a speed run to outpace the media cycle, politics mimics Silicon Valley’s acceleration. The most advanced factories are now “dark”, so fully automated that the supervision of human eyes is a waste of electricity. The blind robots and the electorate cohabit the gloom.

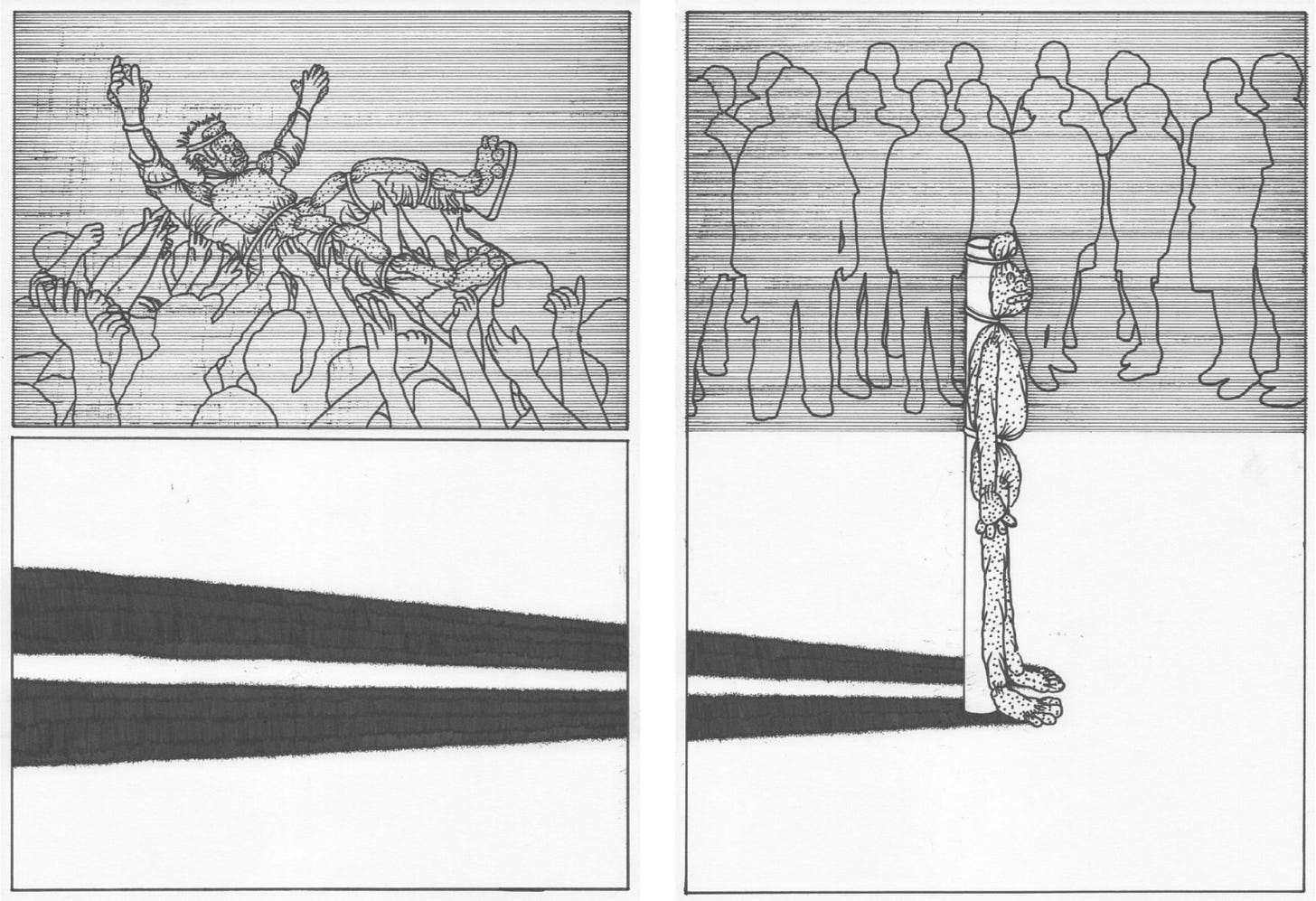

Jefford is making art that can survive in the blackout. Is not the style of his drawings, their sparse line work, conducive to being sent across pirate radio channels at a low bit rate? These are images to be faxed to evade the internet. The narratives themselves are paranoiac; we sense the eerie proximity of a spy or priest lurking offstage, plotting to denounce. In one example, we witness the pandemonium of a mob rousing a scarecrow character. It is disguised in apocalyptic sackcloth or animal fur, like a saint in a hair shirt infested with lice. Swiftly it is carried aloft, exalted as a messiah or dragged to a lynching. Abruptly, the source of the long shadow in the panels below is made evident. Our hero is tied to a stake. The mob, now placid, is waiting, presumably for a volley of ammunition. Noticing the tattered body armour, we have the sense this has happened countless times before. The character is a scapegoat, put through an eternal cycle of punishment.

Authoritarianism takes the ephemeral and makes it obnoxiously concrete. It is noteworthy that UFO sightings are now a major theme in US Congress hearings, a signal that the fantasies and delusions of the masses, no matter how spurious, are being brought under the scrutiny of the militarised state. Reality is discredited not through disavowal but by positive capture; it is an offensive land grab of the imaginal.

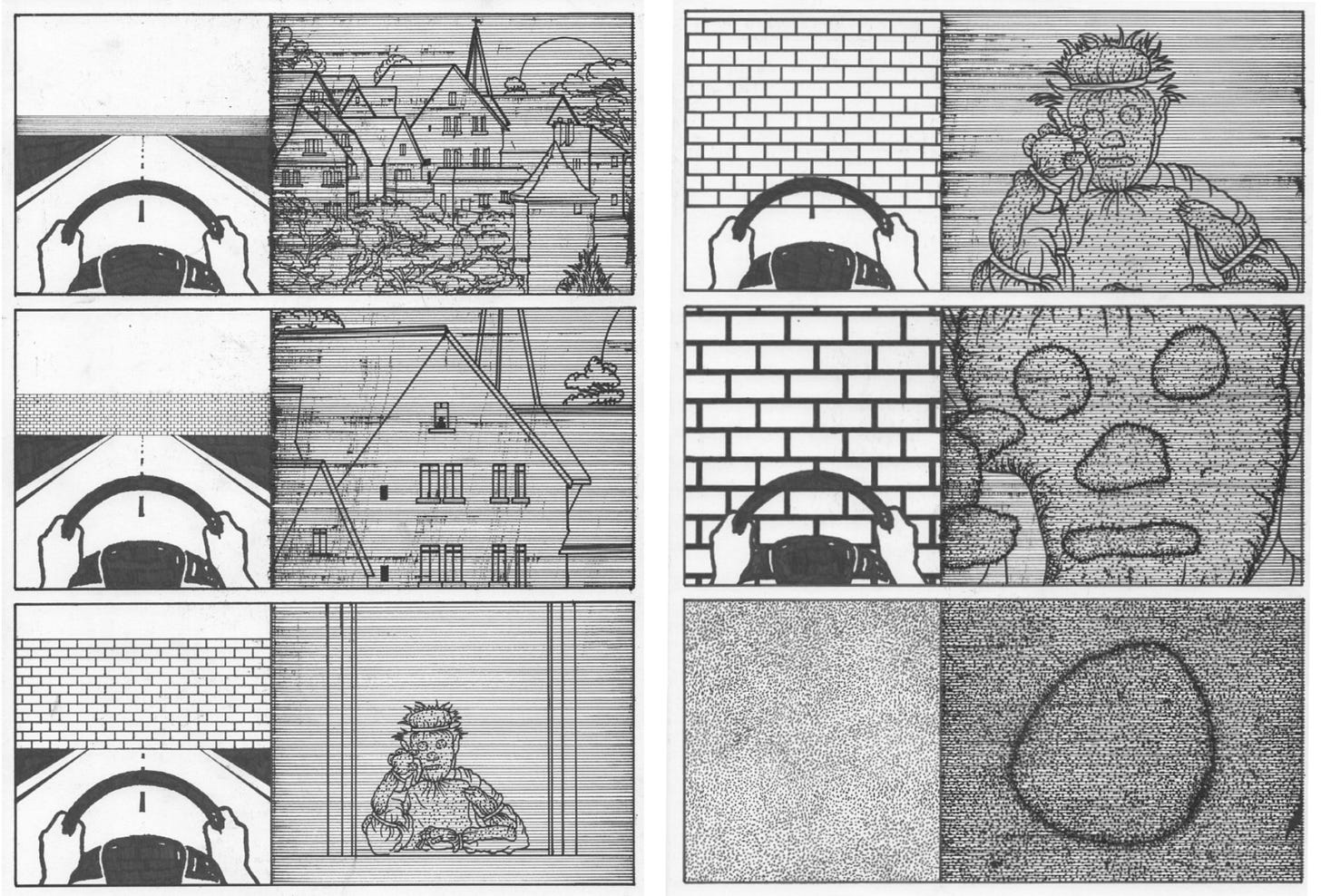

In one of Jefford’s drawings, we witness a body de-evolving; healthy limbs and face bloat, then compress into a smooth frankfurter urform. Immortality of the body, the fantasy of the Fyodorovian cosmists, is shared by Vladimir Putin and the Silicon Valley rationalists alike. The endgame of capitalism has become a grinding mechanical reduction; the virtualisation of the world is the greatest delusion of all.

All that is air condenses back to solidity! Pump more water into the data centre cooling pipes!

An atmosphere of depersonalisation saturates Jefford’s snug and infantile suburbia. He has amputated sections of the ontological render pipeline. Time, selfhood, or causality are erased, yet the remaining code is left running. Degeneration into addictive routines of self-harm wither the incumbent characters. The anxious and dying civilisation is quantified by ad hoc units which have lost synchrony with the world. A Mozart character scratches out numerals, or the crashing of a car forms the metre of a deranged clock. We get the sense that each character is the final human, a singular sane individual, whilst reality itself is ravaged by a vicious dementia.

Detail from ‘Appalling acts of kindness’ 2025